-

London, United Kingdom, December, 2008. Dad at home ready to go out.

Throughout the first years I was photographing him, I mainly shot film. My father would see this with half approval. He was happy I was doing what I wanted to do but I sometimes thought his jokes about it were half serious. "What a waste of film! Don't you have enough pictures of me already? I bet you have taken a few hundreds.". I couldn't tell him that the reason I was photographing him was because I wanted to seal my memories of him (*), with the help of photography. I couldn't tell him that I had to photograph as many things as I could because no one knows how long he had before that dreaded time. So I just smiled and said that I sucked (partly true) so I had to keep on trying. When I finally took photographs in digital, he stopped the critique of "waste of film" and began imaginary counts of the photographs I had taken of him; "there must be four or five thousand by now".

a

Towards his final years, he began to accept the fact that I was almost always taking photographs of him. There were manythings I couldn't, however, take any photographs of, or there are very few of them at best. One of these is that of him walking. I preferred to hold him by his arm when we walked together. The majority of the photographs of him walking were taken when he was roughly 95 or 96.

a

I was reminded of an important lesson in 2008 when he arrived in London see the MA show. I had fun explaining my parents about reportage photography, which had a very vague meaning to them. In order to give my parents an idea, I grabbed some books I have and showed them along with the work I presented as my thesis. I thought that by showing them (to my father especially, the Hungarian Revolution book by Erich Lessing) the scope of work of a reportage photographer, they could then more or less understand reportage photography. The idea of showing Lessing's work in Hungary was a good one because my father was familiar with the subject.

a

* I have come to think he must have known, or at least suspected, that I was taking photographs for that reason.

-

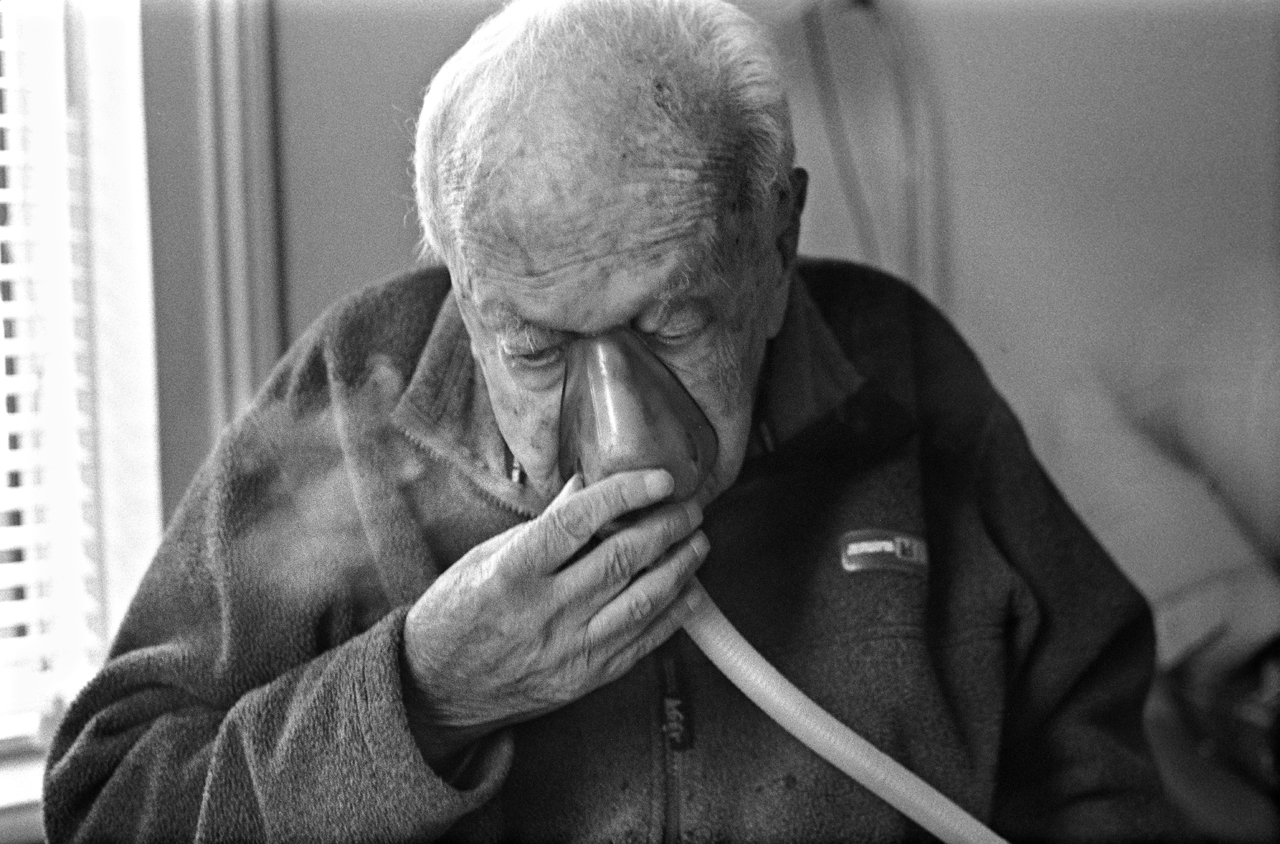

London, United Kingdom, December, 2008. Dad doing his daily nebulisation session in the morning after breakfast.

It did help a bit, but then my father rephrased something he had told me many years ago. He said: "Do what you like to do and you'll be good at it. You must be patient to get anywhere. As long as you do what you like to do, it will all be fine".

a

When I was between 14 and 15 (I graduated school at 17) I asked my father whether he thought I should study architecture - a very profitable busines in the late 1990s in Bolivia - or business in order to continue to manage his company. He said I should do neither and then told me what he repeated back to me some 10 years later. This explained many things about him. This also tied up with another thing he said years ago: "Don't take life too seriously". In short, for him, life was for living as you wanted, otherwise there was no point.

a

It also put his stubborness into perspective. One impotant factor to have in mind was that he did not want to use a walking stick until he really needed one. It was the same with the wheelchair. He finally began to use a walking stick, daily, when he was about 95. Later, he only allowed himself to be in a wheelchair by 98, when he could not walk long distances anymore. I got his wheelchair during one of his visits to London in 2009. He did not like the idea of being pushed around on it. But, he did appreciate the convenience of avoiding some bus journeys in favour of a nice stroll.

a

My father particularly disliked getting onto buses. Buses in London can have very turbulent rides. Especially when braking and accelerating and, depending on the driver, when they steer as well. If we could not walk (because of the weather) then we would take a bus or a taxi, which my father also disfavoured because of their exhorbitant prices. Train was the best way and it is worth noting that it was also my father's favourite form of transport. Sadly enough, though, it was not until I moved to Stratford that we could commute by train. By 2008, my father had difficulty going up the stairs already and most stairs in London, train stations or houses, were too steep for him.

-

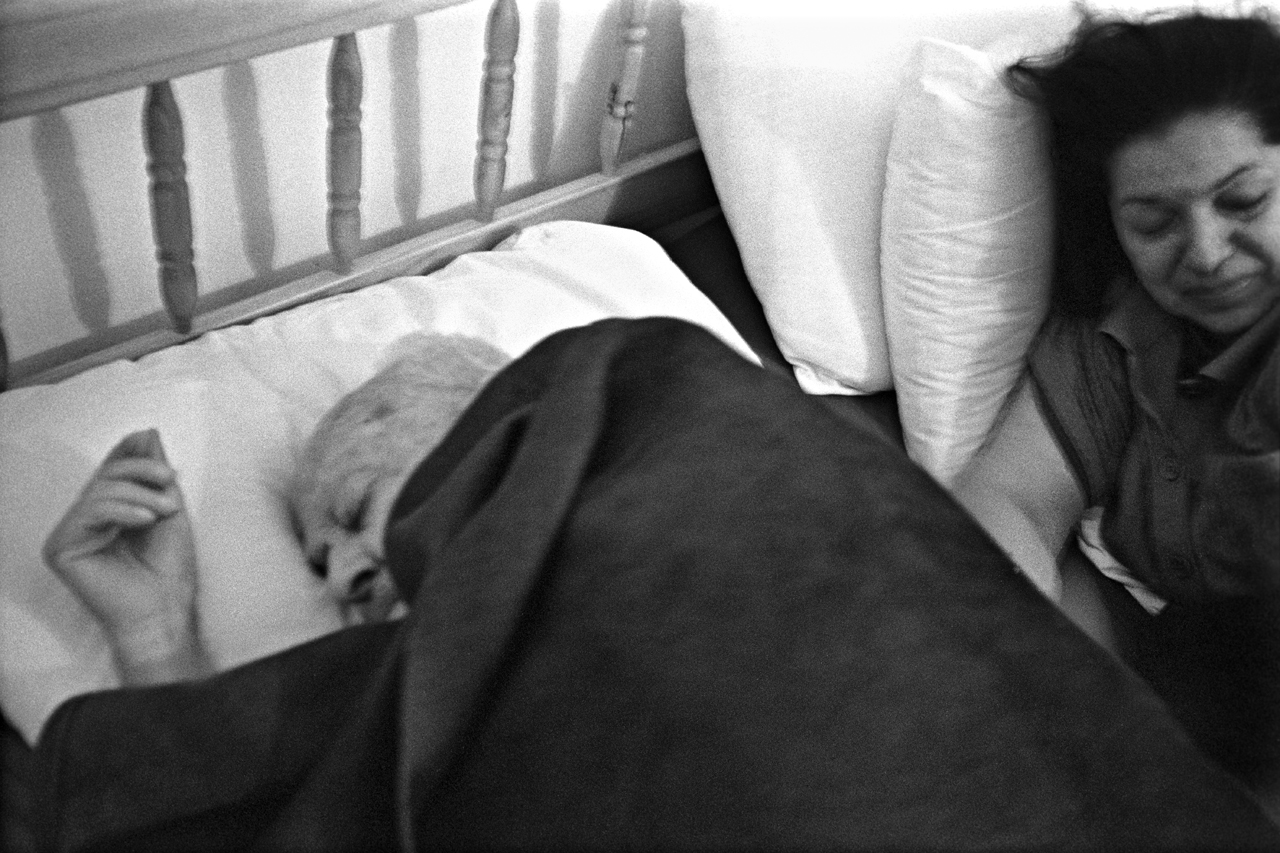

London, United Kingdom, December, 2008. My father and my mother going to sleep.

His mind remained sharp although every time I saw him (when visiting him or when he came to visit me) I would notice a decrease in physical performance. He began to more or less measure his physical performance and stamina by counting the metres he would be able to walk before feeling tired. When he was 96, he could walk a few hundred metres and maybe a km (depending on the weather). By 99, he could not walk more than 150m without requesting a chair, usually his wheelchair. This issue with walking was influenced by his deteriorating balance and pain in his right leg.

-

London, United Kingdom, July, 2009. My father in my living room.

In July 2009, my parents came back to London. In the roughly six and a half months since I last saw my father, his physical performance had reduced considerably. He would also show the first sings of urinary incontinence.

a

This trip was a first step before going to Hungary. It had been four years since he had been to Hungary and by now he was wondering whether he would be fit to see it again after this year.

a

He felt weaker and by now his focus began to slowly shift towards looking after my niece in Florida, who was 5 at the time. My mother also thought the same. They would both then begin preparations to live with my sister in Florida. It was an open schedule and no dates were set.

a

This trip to Hungary would mean a lot for him because he was going to find a long time friend of his back in Szombathely, where he was born. He also wanted to see his parents' memorial tombstone once more.

a

With his mental health looking extremely well, I thought that it was quite likely that he would be able to make another journey back after 2009. I was right.

-

London, United Kingdom, July, 2009. Dad nebulising at my home.

-

Mrs Pippy is a very sweet woman. The last time she saw me and my sister (a long time ago, enough for me not to remember) she remembered that I liked Coca Cola and drank it all the time. There was such a time, indeed, but a long time ago.

a

For this reason, she always had a bottle of Coke ready with every meal. It was a bit strange because I was given Coke to drink by her and my father also insisted I drink his favourite wine at the same time. So it was a wine and Coke time in Szombathely.

a

I learned that after the Second World War, Mrs Pippy had taken care of my father's sister in law. It was something my father never forgot and kept well in touch with her. Throughout many years they exchanged letters until one year my father didn't receive a reply. After a couple of years, he thought the worse. In 2005, the last time we had been in Szombathely, my father and I went to her door and rang the bell. No one answered, so we then assumed the worse.

a

Then, in 2009, I found on the internet that the phone number to the same house was still listed under her name. We gave it a shot and found her alive and well and very excited about our arrival in Hungary. We decided to spend one night in Szombathely as we did not want to cut our stay at her home short because of the train schedules to go back to Budapest.

a

It was a nice time. My father recalled many memories, even the worse ones.

-

Szombathely, Hungary, August, 2009. Dad and Mrs Pippy drinking Debroi Harslevelu, one of dad's favourite wines.

-

Szombathely, Hungary, August, 2009. Mrs Pippy awaiting the departure of our train to take us back to Budapest.